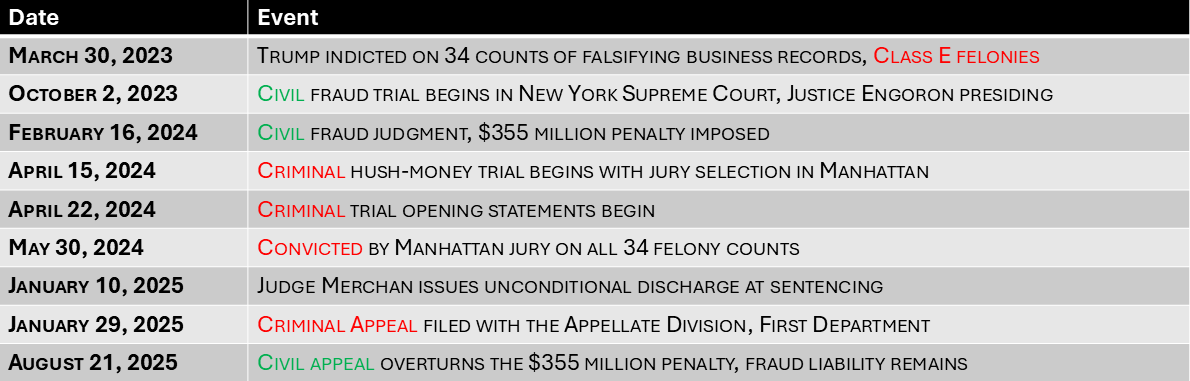

Last week, I responded to a TikTok by Dean Love where he described Donald Trump as a violent felon. That required some correction. To do that, we first have to establish the baseline facts. The fact is this: Donald Trump is a convicted felon. That is not opinion, it is documented, undeniable, and in evidence. It is, however, appealable, and Trump’s legal team has already begun that process.

What surprised me was how many people didn’t understand the distinction between Trump’s criminal conviction and his civil judgment, or even the basic mechanics of conviction. Some insisted you are not “convicted” until sentencing. That is false. In New York, conviction happens when the jury delivers and the court accepts a guilty verdict. Even if we entertained that misconception, Trump has in fact been sentenced. Judge Juan Merchan issued an unconditional discharge in January 2025.

The most important part of any discussion is debating facts, not opinions. This article provides a comprehensive account of Trump’s two major New York cases: the criminal conviction and the civil fraud ruling. It explains how civil and criminal courts differ, the meaning of “unconditional discharge,” the appeals process, the limits of presidential and judicial power, and whether Trump qualifies under law as a violent offender.

Criminal vs. Civil Justice: Core Differences

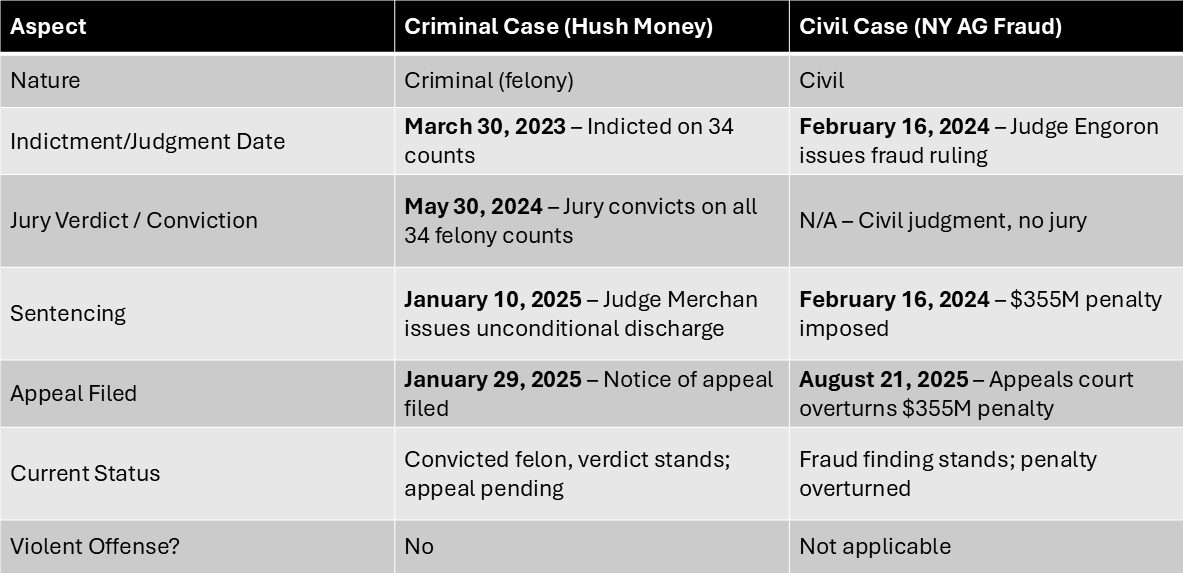

Understanding Trump’s two New York cases requires first drawing a clear line between criminal law and civil law. Although both take place in courts and can involve serious consequences, they serve very different purposes and operate under different standards.

Criminal law is the branch of the justice system where the government prosecutes individuals or organizations for violations of the law that society defines as offenses against the public order. A criminal conviction can lead to the loss of liberty through jail or prison time, as well as probation or other criminal penalties. Because of the gravity of these potential outcomes, the standard of proof is the highest in law: beyond a reasonable doubt. This means jurors must be firmly convinced of guilt before a conviction can be rendered. In Trump’s hush money case, the Manhattan District Attorney’s office represented the state, and a jury was required to unanimously agree on his guilt before he could be convicted.

Civil law, by contrast, typically involves disputes between private parties, or between an individual and the state in its capacity as a regulator rather than a prosecutor. Civil cases can cover a wide range of issues, from contract disputes to fraud claims, as seen in Trump’s civil fraud trial. The potential penalties in civil cases are financial or regulatory: fines, injunctions, or restrictions on business practices. Importantly, civil courts cannot impose imprisonment. Because the stakes are not considered as severe as in criminal cases, the burden of proof is lower. Instead of proof beyond a reasonable doubt, the standard is usually a preponderance of the evidence, which means the judge or jury must find it more likely than not that the defendant is liable.

These differences explain why Trump’s legal exposure took two very different forms in New York. In the criminal case, his liberty and criminal record were on the line, and the state had to meet the strictest burden of proof. In the civil case, his finances and business operations were at risk, and the attorney general only had to show that fraud was more likely than not. Both are serious, but they function differently within the legal system.

Case One - Civil: Fraud Through Asset Inflation

The first of Trump’s two major New York defeats came not in criminal court, but in the state’s civil system. On February 16, 2024, Judge Arthur Engoron issued a sweeping ruling against Trump, his company, and several of its executives. The New York Attorney General had brought the case alleging that Trump repeatedly inflated the value of his properties in order to secure favorable loans and insurance terms. After weeks of testimony and document review, the court agreed, holding Trump liable for civil fraud.

The penalty was severe. Engoron imposed a $355 million fine and barred Trump from running a New York company for three years. This was not a criminal sentence. No jail time was possible in a civil case. The financial and reputational consequences were nonetheless profound. The judgment underscored the lower burden of proof in civil proceedings, where liability must be shown by a preponderance of the evidence rather than beyond a reasonable doubt.

Trump’s legal team immediately pursued an appeal. On August 21, 2025, the New York appellate court issued its ruling. While the judges agreed with Engoron’s finding that fraud had occurred, they found the financial penalty to be excessive and in violation of constitutional protections against disproportionate fines. As a result, the $355 million penalty was overturned.

The fraud finding itself, however, remained intact. Trump and his businesses were still legally recognized as having engaged in fraudulent practices, even though the dollar figure attached to that misconduct had been struck down. In addition, other penalties continue to apply. Trump is barred from running a business in New York for three years, a period that overlaps with his current presidential term. The Trump Organization is prohibited from seeking loans from banks registered in New York. His sons, Donald Trump Jr. and Eric Trump, remain barred from serving in leadership roles within the company.

This outcome illustrates the difference between liability and remedy in civil law. The liability, Trump’s responsibility for the fraudulent conduct, was preserved on appeal. What changed was the scope of the remedy, the financial penalty the court had chosen to impose.

Case Two (Criminal) – Falsifying Business Records

The more historically significant case came from the criminal courts. On March 30, 2023, the Manhattan District Attorney indicted Donald Trump on 34 counts of Falsifying Business Records in the First Degree, a Class E felony under New York Penal Law § 175.10. The charges centered on payments made to Michael Cohen, Trump’s former attorney, which were recorded in the Trump Organization’s books as “legal expenses.” Prosecutors argued these entries were deliberately falsified to conceal reimbursements for hush money payments intended to influence the 2016 election. After a full trial in the spring of 2024, a Manhattan jury returned guilty verdicts on all 34 counts on May 30, 2024. Under New York law, this moment marked Trump’s conviction. A defendant is legally convicted when the jury delivers a guilty verdict and the court accepts it. Sentencing is a separate stage of the process, but the conviction is immediate.

The sentencing phase concluded on January 10, 2025, when Judge Juan Merchan issued an unconditional discharge. This is the most lenient sentence available under New York law: no imprisonment, no probation, and no fine. While unusual in a felony case, it is legally permissible. The unconditional discharge did not erase the conviction; it simply meant the court imposed no punishment. Trump remains a convicted felon despite the absence of a custodial or financial penalty.

Trump’s legal team filed a notice of appeal on January 29, 2025 with the Appellate Division, First Department. From there, the case could move to the New York Court of Appeals, the state’s highest court, and ultimately to the U.S. Supreme Court if federal constitutional issues arise. To date, however, no appellate court has ruled on the conviction itself. The only involvement of the U.S. Supreme Court came in January 2025, when Trump asked the justices to delay his sentencing while he pursued arguments about presidential immunity. The Court rejected the request, allowing Judge Merchan to proceed with sentencing. Importantly, the Court did not address the merits of the conviction or the underlying legal theory.

Sidebar: Dispelling Common Rumors

In the course of writing and talking about these cases, several recurring claims and pushbacks have surfaced. It is important to separate speculation from fact.

Rumor 1: “Trump isn’t a convicted criminal until he’s sentenced.”

This is false. In New York, conviction occurs the moment a jury returns a guilty verdict and the court accepts it. Sentencing is a separate step. Even if that claim were true, Trump was sentenced on January 10, 2025, when Judge Merchan issued an unconditional discharge.

Rumor 2: “The convictions were overturned by the Supreme Court.”

This is also false. Trump’s criminal convictions have not been overturned by any court. The U.S. Supreme Court only ruled on a narrow question in January 2025, when it denied Trump’s request to delay sentencing. The merits of the conviction have not been reviewed.

Rumor 3: “The civil penalty was thrown out, so Trump was cleared of fraud.”

Incorrect. The appellate court overturned the $355 million penalty as excessive, but the fraud finding itself remains intact. Trump is still legally recognized as having engaged in fraudulent practices. Other restrictions, such as the three-year bar on running a business in New York, the ban on seeking loans from New York-registered banks, and leadership bans on Donald Jr. and Eric Trump, are still in place.

Rumor 4: “Trump is a violent felon.”

Not under any legal definition. Trump’s convictions are for falsifying business records, a nonviolent white-collar crime. Federal law classifies violent felonies as crimes such as assault, robbery, or murder. Trump is a convicted felon, but he is not classified as a violent offender.

Rumor 5: “New York only prosecuted him because it’s a blue state.”

The political leanings of New York are often invoked in this argument, but they are not relevant to the legal process. Both the civil and criminal cases were handled under existing New York statutes. Trump had access to due process, legal representation, and the appeals system that is available to every defendant.

Rumor 6: “These should not have been charged as felonies.”

This is the big one. Out of all the pushback, this argument has been repeated the most, and it deserves careful explanation. The claim is that Trump should never have faced felony charges because prosecutors did not prove an underlying crime, and Trump himself had never been convicted of any such crime before.

Here is how New York law actually works. Falsifying business records is usually a misdemeanor. It becomes a felony when the records are falsified with intent to commit another crime, or to aid or conceal the commission of another crime. The important detail is that prosecutors do not have to prove that the other crime was successfully carried out. They only have to prove that the falsification was done with the intent to commit or cover up some criminal act. That is enough to elevate the charge from misdemeanor to felony.

This is where the controversy arises. At Trump’s trial, the judge instructed the jury that they all had to unanimously agree Trump falsified records with criminal intent, but they did not need to agree on the exact underlying crime. Some jurors may have believed the intent was tied to a campaign finance violation, while others may have believed it was tied to a state election law violation or a tax law issue. Critics argue that this diluted the requirement for unanimity, since the jurors were allowed to reach a guilty verdict even if they differed on the exact crime Trump intended to conceal.

Legal experts note that this approach is permitted in New York, but it is unusual in such a high-profile case. The fact remains that Trump was not required to have a prior conviction for an underlying offense in order for his business records charges to be elevated to felonies. The law only requires intent, not proof of a completed or separately adjudicated crime.

So while the argument that “these should not have been felonies” resonates with Trump’s defenders, under New York’s statutes the elevation was legally permissible. The controversy rests less on whether the law was followed and more on whether the way the jury was instructed created confusion or lowered the bar for a unanimous verdict.

Felony Yes, Violent Offender No

Donald Trump is, without question, a convicted felon. That status became official on May 30, 2024, when a Manhattan jury returned guilty verdicts on 34 counts of falsifying business records and the court accepted the verdict. Conviction in New York does not wait until sentencing. It occurs at the moment the jury’s decision is rendered and entered into the record. Even though Trump later received an unconditional discharge at sentencing, the conviction itself remains intact.

Where confusion often arises is in the label of “violent offender.” Some commentators have inaccurately described Trump as a violent felon. That is incorrect. Falsifying business records is a white-collar crime. It is classified as a Class E felony, but under both federal and state standards it is not considered a violent offense. Violent felonies include crimes such as assault, rape, robbery, and murder. Trump’s conviction falls entirely outside that category.

The distinction matters. Being a convicted felon carries real consequences in terms of status, rights, and reputation. But being labeled a violent offender carries an additional weight in the justice system that does not apply here. Trump is a convicted felon, but he is not and has never been classified as a violent offender.

Conclusion: Facts vs. Opinions

Donald Trump’s legal record in New York is not a matter of speculation. He was convicted of 34 felonies in a criminal court, and he was found liable for fraud in a civil court. Those are the facts. They are recorded in verdicts, judgments, and appellate rulings.

Facts and opinions live in different lanes; to acknowledge the facts is not to dismiss opinion. People are free to argue that the charges should never have been brought, or that the penalties were too harsh, or that the law was applied unfairly. Those are valid discussions, but they are separate from the reality of what has already taken place.

There is a difference between what did happen and what someone believes should or should not have happened. Both conversations can exist, but they cannot be collapsed into each other. Acknowledging the historical and legal record does not prevent debate over fairness or politics, nor does it mean agreement with the outcome. What it does is draw a clear line between evidence and interpretation, between the courtroom record and the court of public opinion.